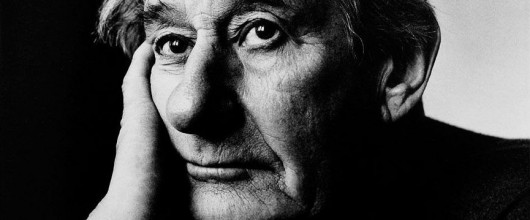

Helmut Newton – pioneer fashion nude photographer

HELMUT NEWTON pushed back the boundaries of nude photography and became one of the most recognizable figures in the fashion world. He broke the mold by remaining at the forefront of visual style for several decades – a rarity in the fashion and publishing business. But through it all he never forgot he was a refugee who fled Nazi Germany and he got his first break as a photographer in Australia, the most unpretentious nation on the planet.

There is, though, a mystery; a contradiction. Newton disliked being described as an artist. Yet his photographs provide some of the most memorable art of the last half century. He said he had no interest in the inner life of his sitters “ “just their bosoms, bums and legs.” Yet, a Newton photograph captures private moments, private lives, a chilling sense that we are glimpsing raw, unprotected souls. You could say that the nude in Newton’s work is merely a metaphor for the nakedness of being.

Newton reveals in naked women a look of indifference, yet an acceptance of everything, their pride, their flesh, their sexuality, a touch of arrogance. His models show no weakness or doubt; they are distant yet available and distil unexplored moments of a woman’s life as if the camera isn’t there. “The challenge,” he once said, “is to show something more of who that woman is.”

‘… a Newton photograph captures private moments, private lives, a chilling sense that we are glimpsing raw, unprotected souls’

Beautiful women with no financial incentive to be photographed naked often had an impulse to reveal themselves to Helmut Newton. Sigourney Weaver, Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, Jerry Hall, Charlotte Rampling, Catherine Deneuve. “He has the quality of Matisse and the eye of the voyeur,” Deneuve once said, the quality I would say that transforms his work from being merely recognizable to being unique.

Charlotte Rampling thinks of Newton as a movie director who chose to shoot stills. His photographs tell a story; you want to know what just happened and what’s going to happen next. “Still photography is like being brought to a climax, then you stop and start again,” said Rampling. “The experience is frustrating and creates for me an erotic melancholy.”

Newton didn’t merely photograph women, it was a collaboration. The sensual, melancholic experience described by Rampling is the petite mort that lingers between lovers and this undeniable familiarity is captured in every sequence of shots as if his life’s work is the documenting a continuous love affair. You cannot imitate a Newton portrait. Given the same light, the same model, the same pose, when Newton was behind the shutter he would conjure up an ambiguity, something unseen or indefinable.

Would he have appreciated this analysis? He would no doubt have laughed in his distinctive way and got on with taking another photograph. Photography was his passion, his obsession: the unending love affair. He told June, his wife to be, when they first met in Australia in 1948 that she would always be his second love. It was the basis for the perfect marriage and for fifty years she was his partner, his PA, his sounding board and his model.

Helmut Newton was born to a well-off family in Berlin in 1920, the Roaring Twenties, skirts were getting shorter, women were savouring the first taste of liberation. Young Helmut recalls appreciating the bare arms of his beautiful mother in a cocktail dress and would lie in bed watching the maid in the next room naked from the waist up combing her hair. He adored women. He called his autobiography World Without Men. It was the world he constructed in his mind as a boy and lived in as a man.

His father was a button manufacturer who would have liked his son to go into the family business but gave him a camera as a birthday present at the age of twelve and set the wheels of his son’s destiny in motion. Helmut dropped out of school and went to work as an apprentice with fashion photographer Yva, learning his craft in the dark room and fantasising about the beautiful women in tight skirts and stiletto heels clipping along the Kurfurstendamm. He never lost his love of black high heels.

Newton was a Jew. When the horrors of Kristallnacht awoke his parents from their tenuous sense of security in Hitler’s Germany, they fled into exile. His family sailed to South America, while Helmut went alone to the Far East. He would never see his parents again.

From Singapore, Newton moved on to Australia with an expired German passport and was promptly interred as an enemy alien. He went from prison camp into army uniform and served with an Australian regiment four years as an enlisted soldier. He was tireless in his passion to take photographs and shot hundreds of rolls of film, battle scenes and portraits of men in combat.

He grew lean and handsome and discovered after the war a taste for silk shirts and fine living he subsidised more through his role as a gigolo than the shutter action of his camera. But the camera was always present, the emblem of his identity: the tool of his ambition. His early flight from Germany and separation from his family had forced him into a nomadic, independent existence that drove him relentlessly all through his life.

For all its size, Australia was too small for Helmut Newton and he returned to Europe. He lived first in England, but found the country and its people too cold, too closed. His move across the Channel to Paris was the beginning another love affair that would last the rest of his life. Paris was an inspiration, the city of artists and crystal light: the smell of warm croissants a haunting memory of the bakeries in pre-war Berlin, the fluttering display of short skirts on the Champs Elysee a mirror image of the girls on the Kurfurstendamm.

In the dark room in Berlin he had dreamed of being a Vogue photographer and when he got the opportunity to join French Vogue in 1961, he staged fashion shoots in a way that was new, daring, controversial and made him an instant success. He took models out of the studio to use natural light and used locations where you would least expect to find the latest fashions. The styles of those times have not survived – such is fashion – but Newton’s images remain as fresh as ever.

Newton’s lifetime objective to push back the boundaries of photography had begun. The Berlin he remembered was a city of shifting shadows and a damp diffused light that informed his photography wherever he travelled and created a mood of sensuality and decadence. He became legendary for his risqué shots of fashion models. His nudes evoked the louche cabarets of the thirties. As if haunted by those times, he shot nudes in belle epoch ballrooms and fading hotel rooms swagged in velvet drapes and lit by chandeliers. His photographs were a banquet, a feast, a celebration of life.

‘he said once that there are two dirty words in photography: good taste and art’

Helmut Newton took every assignment he was offered. He liked the money, enjoying the luxury as well as the freedom that money brought, and while his work was now moving from the magazine pages to the gallery walls, he never considered the suggestion then in vogue of creating installations or accepting commission from museums. In his distinctive English, he said once that there are two dirty words in photography: good taste and art.

He was, in his own words, a gun for hire. He worked ceaselessly for a decade, moving between the four corners of the box that made up his life: France, Monaco, Germany and Los Angeles. He adored the movies. His life was a movie, non-stop action, another take and another, and he suffered the consequence in 1971 when he was rushed into hospital with a heart attack.

Did he imagine time was running out? He make a surprisingly quick recovery and was anxious to get back to work. He sent out for an automatic camera and began shooting the doctors, the staff, his visitors, and when he came out of hospital he made one concession to his schedule: he began to tell the couturiers (“They’re all prima-donnas!”) what he wanted to shoot and they either accepted or they found a different photographer.

Newton’s work was becoming consistently more audacious, more erotic. In 1976, he published White Women, a declaration of intent that established him as the agent provocateur of the fashion world. So distinct were his images, they became a Vogue hallmark: the gold standard other photographers were expected to reach.

From his early days as a gigolo, Newton continued to lead a fast, decadent lifestyle reflected in his photography. He had innumerable affairs that he spoke of with narcissism, but as a photographer his work not his affairs took pride of place. Like Matisse, as Catherine Deneuve has said, the magic of Helmut Newton’s work is its elusiveness, its sly refusal to admit the true nature of its subject matter: the failure of reality and the triumph of desire. Beautiful women know they are desirable. They know their beauty inspires the imaginations of men. That is why the world’s most beautiful women in recent decades who chose to strip for the camera chose Helmut Newton’s camera to pose for.

Newton’s work has appeared in every major publication from glossy art books to Vogue to Playboy, whose founder Hugh Heffner called him as a giant. “He was a major talent who pushed the boundaries in terms of photography and influenced many, many other photographers in following generations.”

The English author of Crash, JG Ballard, has described Newton’s photography as being as vivid as tomorrow’s news, which in one way it always has been. “Though his clients and their advertising agencies would be appalled by the thought, I imagine that few people coming fresh to Newton’s work would suspect that the nominal purpose of these striking images was to sell a collection of high-priced frocks.”

But then Newton has always been much more than a fashion photographer. “I think of him,” adds Ballard, “as a figurative artist who uses the medium of photography, and his access to gorgeous women, expensive gowns, and exotic locations, to create a unique imaginative world.”

While work by many of Newton’s contemporaries now seems rooted in their own time, trite or quaint; Andy Warhol is one example, Newton’s photography remains fresh, as poetic and mysterious as when it first appeared. Nude photography has always provoked disapproval. The censors are always there to wrap dark cloaks over what they perceive as sexual voyeurism. They look at the surface of such work without recognizing the enchantment: the artistry. Far from demeaning or humiliating his models, Helmut Newton placed them at the heart of his own desires, in a world where they rule with pride and passion, something the models understood, even if the critics did not.

Helmut Newton died in 2004 at the age of 83. He left the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood driving his Cadillac. He lost control and crashed into a wall, a movie ending he probably would have appreciated.

Text Source: photoicon.com